MSX2-Technical-Handbook

CHAPTER 3 - MSX-DOS

Large capacity storage devices with high-speed access are necessary for business applications. That is why a disk operating system was added to the MSX machine. The DOS (disk operating system) is also required to handle the large amount of data on the disk effectively. MSX-DOS is derived from MS-DOS which is used widely on 16-bit machines. Thus, it represents the most powerful DOS environment for Z-80 based machines. Chapter 3 describes the basic operations of MSX-DOS and the use of the system calls.

Index

4.2 Environment Setting and Readout

4.3 Absolute READ/WRITE (direct access to sectors)

1. OVERVIEW

What kind of software is MSX-DOS? What does it offer to users? The following sections describe and introduce the features, functions, and software configurations of MSX-DOS.

1.1 Features of MSX-DOS

Consolidation of disk operating environment

MSX-DOS is the disk operating system for MSX computers. It works with any version of MSX and can be operated on both the MSX1 and MSX2 without any problem. Disk operation on MSX is always done via MSX-DOS. This is also true concerning MSX DISK-BASIC, which uses BDOS calls for disk input/output. MSX-DOS and DISK-BASIC use the same disk format so that file conversion between BASIC and DOS is not necessary. This greatly increases operating efficiency and allows more effective use of file resources when MSX-DOS is used as the software development environment.

Compatibility with MS-DOS

MSX-DOS, created on the basis of MSX-DOS (ver 1.25) which is a disk operating system for 16-bit personal computers, uses the same file format as MS-DOS. It is compatible with MS-DOS at the file level so that MSX-DOS can read and write files written on MS-DOS disks. In turn MS-DOS can read and write files created by MSX-DOS. Both disk operating systems use similar commands, so users who are familiar with MSX-DOS can easily use MS-DOS when upgrading to 16-bit machines.

Using CP/M applications

MSX-DOS has system call compatibility with CP/M and can execute most programs created on CP/M without any modification. Most CP/M applications can thus be easily used with MSX-DOS. This opens up a large library of existing software which can be run on the MSX machines.

1.2 MSX-DOS Environment

System requirements

To use MSX-DOS, a minimum configuration of 64K bytes RAM, a CRT, one disk drive, and a disk interface ROM is required. If less than 64K bytes RAM is installed, MSX-DOS cannot be used. MSX computers can only use MSX-DOS if they have 64K bytes RAM or more. Since MSX2 computers always have 64K bytes or more of RAM, they can always run MSX-DOS. A limited disk basic is used on those machines with less than 64K bytes RAM. Disk interface ROM is always supplied with the disk drive, and, on MSX machines with an internal disk drive, it resides inside the machine. For those machines using disk cartridges, it is in the cartridge.

System supported

MSX-DOS supports up to eight disk drives. On a one-drive system, it has a 2-drive simulation feature (it uses one drive as two drives by replacing diskettes temporarily). It supports keyboard input, screen output, and printer output.

Media supported

MSX-DOS, which has a flexible file manager that does not depend on the physical structure of the disk, supports various media and uses 3.5 inch double density disks as standard. Either a one-sided disk called 1DD or two-sided disk called 2DD is used. Each of them uses either an 8-sector track format so four kinds of media can be used. The Microsoft formats for these four types are shown below.

Table 3.1 Media supported by MSX-DOS

----------------------------------------------------------------------

| | 1DD, 9 | 2DD, 9 | 1DD, 8 | 2DD, 8 |

| | sectors | sectors | sectors | sectors |

|----------------------------+---------+---------+---------+---------|

| media ID | 0F8H | 0F9H | 0FAH | 0FBH |

| number of sides | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| tracks per side | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| sectors per track | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| bytes per sector | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 |

| cluster size (in sectors) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| FAT size (in sectors) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| number of FATs | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| number of recordable files | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 |

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Note: See Section 3 for the meanings of the above words.

1.3 MSX-DOS System Resources

Memory map

MSX-DOS consists of the following modules: COMMAND.COM, MSXDOS.SYS, and a disk interface ROM. It resides in memory as shown in Figure 3.1 when MSX-DOS is active. COMMAND.COM and MSXDOS.SYS are disk files until MSX-DOS is booted and then read into RAM after that. Disk interface ROM includes a disk driver, DOS kernel, and DISK-BASIC interpreter.

Figure 3.1 MSX-DOS memory map

0000H -----------------------

| system scratch area |

0100H |---------------------| --- 4000H ---------------------

| | ^ | disk driver |

| | | | DOS kernel |

| | | | DISK BASIC |

| | | | interpreter |

| | TPA 7FFFH ---------------------

| | |

| | | disk interface ROM

|---------------------| |

| COMMAND.COM | V

(0006H) |---------------------| ---

| MSXDOS.SYS |

|---------------------|

| work area |

FFFFH -----------------------

The area 00H to FFH of RAM is called the system scratch area, which is used by MSX-DOS for exchanging data with other programs. This area is important when using system calls, which are described later. The area which begins at 0100H and ends where the contents of 0006H of RAM indicates is calles the TPA (Transient Program Area). This area is accessible by the user. MSXDOS.SYS always resides at a higher address than TPA (when destroyed, the result is unpredictable), and COMMAND.COM is placed in TPA.

COMMAND.COM

The main operation of MSX-DOS is to accept typing commands from the keyboard and execute them. In this case the program COMMAND.COM is responsible for the process from getting a string to interpreting and executing it, or accepting commands from the user interface. Programs executed by COMMAND.COM consists of internal commands, batch commands, and external commands.

Internal commands are inside COMMAND.COM and on RAM. Typing an internal acommand causes COMMAND.COM to call and execute it immediately.

For the external command, COMMAND.COM loads the routine from disk to TPA and executes it (the execution of external commands always begins at 100H). In this case COMMAND.COM frees its own area for the external command. That is, COMMAND.COM might erase itself and writes the external command onto it, when the external command is small enough and does not use the high-end of TPA, COMMAND.COM would not be destroyed. When the external command ends with “RET”, MSXDOS.SYS examines whether COMMAND.COM has been destroyed (by using checksum) and, if so, re-loads COMMAND.COM onto RAM and passes the control to COMMAND.COM.

Batch commands are carried out by getting command line input from a batch file instead of from the keyboard. Each step of the batch file can execute any internal command or external command. It is possible that the batch command executes another batch command, but the control will not return to the caller after the called batch command is done.

MSXDOS.SYS

MSXDOS.SYS, core of MSX-DOS, controls disk access and communications with peripherals. These MSXDOS.SYS functions are opened as “BDOS (Basic Disk Operating System)” so that the user can use them. Each routine opened is called a “system call”, which is useful in developping software for managing the disk (see section 4). Each execution is, however, not done by MSXDOS.SYS itself but DOS kernel. MSXDOS.SYS is an intermediation which arranges input/output requests from COMMAND.COM or external commands and passes them to the DOS kernel.

MSXDOS.SYS includes a portion called BIOS other than BDOS, as shown in Figure 3.2. BIOS, which has been prepared to be compatible with CP/M, is not normally used.

Figure 3.2 MSXDOS.SYS

-------------- --+

| BDOS | |

|------------| | MSXDOS.SYS

| BIOS | |

-------------- --+

DOS kernel

The DOS kernel is the fundamental input/output routine which resides in the disk interface ROM and executes BDOS functions of MSXDOS.SYS. Actually, any system call function can be executed using the DOS kernel. DISK-BASIC executes system calls by calling the DOS kernel directly.

Procedure for invoking MSX-DOS

MSX-DOS is invoked by the following procedure:

-

Resetting MSX causes all the slots to be examined first, and when two bytes, 41H and 42H, are written in the top of the examined slot, the slot is interpreted as connected to a certain ROM. When connected with ROM, the INIT (initialize) routine whose address is set to the header portion of ROM is carried out. In the case of the INIT routine of the disk interface ROM, the work area for the drive connected to the interface is allocated first.

-

When all slots have been examined, FEDAH (H.STKE) is then referred to. Unless the contents of this address is C9H (unless a certain routine is set to the hook of H.STKE during INIT routine), the environment for DISK-BASIC is prepared and execution jumps to H.STKE.

-

When the contents of H.STKE is C9H in the examination above, the cartridge with TEXT entry is searched in each slot and, if found, the environment for DISK-BASIC is prepared, and then the BASIC program at the cartridge is carried out.

-

Then, the contents of the boot sector (logical sector #0) is transferred to C000H to C0FFH. At this time, when “DRIVE NOT READY” or “READ ERROR” occurs, or when the top of the transferred sector is neither EBH nor E9H, DISK-BASIC is invoked.

-

The routine at C01EH is called with CY flag reset. Normally, since code “RET NC” is written to this address, nothing is carried and the execution returns. Any boot program written here in assembly language is invoked automatically.

-

RAM capacity is examined (contents of RAM will not be destroyed). Less than 64K bytes causes DISK-BASIC to be invoked.

-

The environment for MSX-DOS is prepared and C01EH is called with a CY flag set. MSXDOS.SYS is loaded from 100H, and the execution jumps to 100H. After this, MSX-DOS transfers itself to a high order address. If MSXDOS.SYS does not exist, DISK-BASIC is invoked.

-

MSXDOS.SYS loads COMMAND.COM from 100H and jumps to its start address. COMMAND.COM also transfers itself to a high order address and then begins to execute. If COMMAND.COM does not exist, the message “INSERT A DISKETTE” appears and the execution waits for the correct diskette to be inserted in the drive.

-

At the first boot for MSX-DOS, when a file named “AUTOEXEC.BAT” exists, it is carried out as a batch file. When MSX-DOS is not invoked and DISK-BASIC starts, if a BASIC program named “AUTOEXEC.BAS” exists, it will be carried out.

2. OPERATION

This section describes how to type command line input from the keyboard. This is the basis of MSX-DOS operations. Several examples of actual use and their explanations will be given for the commands used in MSX-DOS.

2.1 Basic Operations

Message at startup

When MSX-DOS is invoked, the following message appears on the screen:

Figure 3.3 Screen at atartup

The upper two lines show the version of MSXDOS.SYS and its copyright. The last line shows the version of COMMAND.COM.

Prompt

Then, a prompt (input request symbol) appears under the version description. The prompt for MSX-DOS consists of two characters: the default drive name plus “>”.

Default drive

The term “default drive” as the first character of the prompt is the drive to be accessed automatically when the drive name is omitted. When the default drive is A, for example, referring to a file “BEE” on drive “B” needs to be typed as “B:BEE”. A file “ACE” on drive A, however, can be typed simply as “ACE” omitting the drive name.

ex.1) A>DIR B:BEE (⟵ referring to "BEE" on drive B)

ex.2) A>DIR ACE (⟵ referring to "ACE" on drive A)

Changing default drive

When using systems with more than one drive, typing “B” causes the default drive to be changed to B. When changing the default drive to C to H, “C” or the appropiate letter is needed. Specfification of a drive which does not exist causes an error.

ex.1) A>B:

B> (⟵ Default drive has been changed to B)

ex.2) A>K:

Invalid Drive Specification

A> (⟵ Drive K does not exist. Default drive is not changed.)

Command input

When a prompt is displayed it indicates that MSX-DOS requests a command to be input. By typing in a command, MSX-DOS can get an instruction.

Three forms of commands exist as shown in Table 3.2. The COMMAND.COM program interprets and executes these commands. MSX-DOS operations are repeats of the actions “give a command - make COMMAND.COM execute it”.

Table 3.2 Three forms of commands

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

| (1) Internal | Command inside COMMAND.COM. Assembly routine on RAM. |

| command | Thirten commands are prepared as described later. |

|--------------+--------------------------------------------------------|

| (2) External | Assembly routine on disk. It is loaded from disk at |

| command | execution. Its file name has an extension "COM". |

|--------------+--------------------------------------------------------|

| (3) Batch | Text file containing one or more commands. Commands |

| command | are executed orderly (batch operation). File names |

| | have the extension "BAT". |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

File name convention

Files handled by MSX-DOS are expressed by a “file spec” which is described below:

(1) File spec is expressed in the form <drive>:<file name>.

(2) <drive> is a character from A to H. When specifying the default drive, it can be omitted as well as the colon “:” following it.

(3) <file name> is expressed in the form of <filename>.<extension>.

(4) <filename> is a string containing one or more (up to 8) characters. When more than 8 characters are sepcified, the ninth and subsequent characters are ignored.

(5) <extension> is a string containing up to 3 (including zero) characters. When more than 3 characters are specified, 4th and subsequent chartacters are ignored.

(6) <extension> can be omitted as well a preceding period “.”.

(7) Characters which are available in <filename> and <extension> are shown in Table 3.3.

(8) Cases are not sensitive. Capital letters and small letters have the same meaning.

Table 3.3 Available characters for file name

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Available | A to Z 0 to 9 $ & # % ( ) - @ ^ { } ' ` ! |

| characters | characters corresponding to character codes 80H to FEH |

|-------------+-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Unavailable | ~ * + , . / : ; = ? [ ] |

| characters | characters corresponding to character codes 00H to 20H and 7FH, FFH |

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wildcards

Using a special character called a “wildcard” in the description of <filename> and <extension> of the file specification causes files with common characters to be specified. Wildcards are “?” and “*”.

(1) "?" is a substitution for one character.

ex) "TEXT", "TEST", "TENT" ⟵ "TE?T"

"F1-2.COM", "F2-6.COM" ⟵ "F?-?.COM"

(2) "*" is a substitution for a string with any length.

ex) "A", "AB", "ABC" ⟵ "A*"

"files with an extension .COM" ⟵ "*.COM"

"all files" ⟵ "*.*"

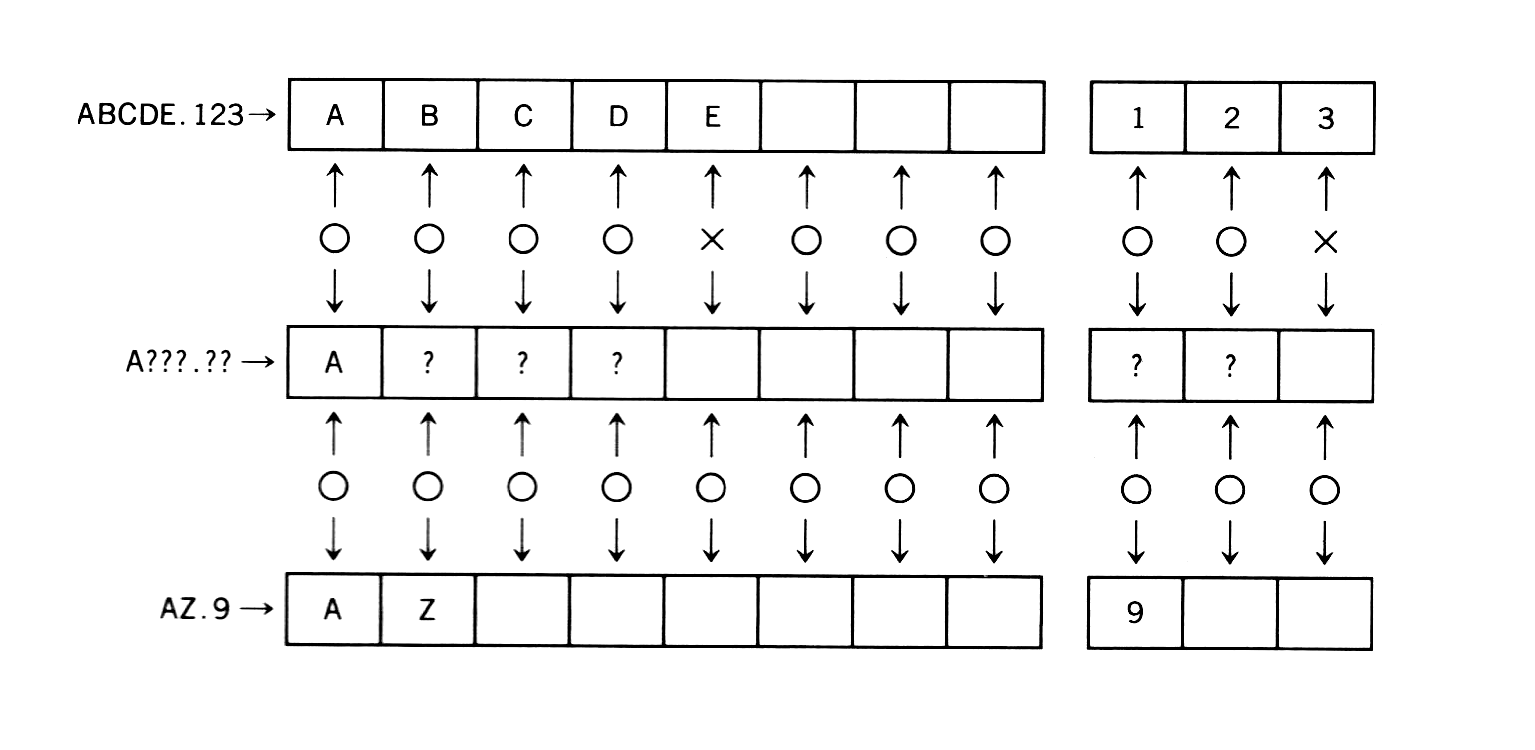

When comparing existing file names and file names with wildcards, the portion less than 8 characters of <filename> and the portion less than 3 characters of <extension> are considered to be padded with spaces (“ “). Thus, a specification “A???.??” is not expanded to “ABCDE.123” but to “AZ.9”, as shown in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 Wildcard expansion

An asterisk (*) is interpreted as either 8 question marks or 3 question marks (?) depending on if it is in the file name position or file extension position. For example, a file name “A*B” is not interpreted as “any strings which begin with A and end with B”. It is interpreted as “any strings which begin with A”, as shown below.

A*B ("*" is expanded to 8 "?"s)

|

V

A????????B (Characters after 8th are deleted)

|

V

A???????

Device name

MSX-DOS does not need special commands for data input/output with peripherals. This means that it considers each objective device as a certain file (device file) and input/output actions are done by reading or writing to or from this file. This enables MSX-DOS users to treat input/output devices in the same way as files on a disk. Five devices are supported as standard by MSX-DOS as shown in Table 3.4 and are specified with proper names. For this reason, these names can not be used to specify disk files. These device names with drive specifications or extensions are also treated as simple device names.

Table 3.4 Device names

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Device name | Input/output device to be specified |

|-------------+----------------------------------------------------------|

| | Reserved name for input/output expansion |

| AUX | which normally has the same effect as NUL |

| | |

|-------------+----------------------------------------------------------|

| | |

| CON | Console (keyboard for input, screen for OUTPUT) |

| | |

|-------------+----------------------------------------------------------|

| | |

| LST | Printer (ouput only; cannot be used for input) |

| | |

|-------------+----------------------------------------------------------|

| | |

| PRN | Printer (same as LST) |

| | |

|-------------+----------------------------------------------------------|

| | Special device used as a dummy when the result is not |

| NUL | desired to be displayed on the screen or put in a file. |

| | When used for input, always EOF. |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Input functions using a template

A “template” is a character buffer area and can be used for command input. The template contains the previous command line most recently entered. It is possible to use the template for easier command entry. By taking advantage of this template feature, it is easy to execute previous commands again or to execute the command partially modified. The keys listed in Table 3.6 are used for the template operation.

Other special keys

In addition to the template operation keys, the following control keys are also available. These special key functions also support some other system calls described later.

Table 3.5 Special key functions

---------------------------------------------------------------

| | Function |

|-------+-----------------------------------------------------|

| ^C | stops command currently executed |

| ^S | pauses screen output until any key is pressed |

| ^P | send characters to the printer at the same time |

| | they appear on the secreen |

| ^N | resets ^P and send characters only to the secreen |

| ^J | feeds a line on the screen and continue input |

---------------------------------------------------------------

Table 3.6 Template functions

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Name | Keys used | Functions |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| COPY1 | RIGHT, ^\ | Gets one character from the template and |

| | | displays it in the command line |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| | | Gets characters before the character to be |

| COPYUP | SELECT, ^X | typed next (by keyboard) from the template |

| | | and displays them on the command line |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| | | Gets all characters from the location which |

| COPYALL | DOWN, ^_ | the template is currently referring to the |

| | | end of the line and displays them on the |

| | | command line |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| SKIP1 | DEL | Skips one character of the template |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| SKIPUP | CLS, ^L | Skips template characters before the |

| | | character to be typed next (by keyboard) |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| VOID | UP, ESC, ^^, | Discards current line input not changing |

| | ^U, ^[ | the template |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| | | Discards one character input and returns |

| BS | LEFT, BS, | the location referred by the template |

| | ^H, ^] | by one character |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| | | Switches insert mode/normal input mode, |

| INSERT | INS, ^R | in insert mode, displays keyboard input |

| | | on the command line with fixing the |

| | | location referred by the template |

|----------+--------------+---------------------------------------------|

| NEWLINE | HOME, ^K | Transfers the contents of current command |

| | | line to the template |

|-------------------------+---------------------------------------------|

| | Feeds a line on screen but continues |

| Return | getting input. Transfers the contents of |

| key | current command line to the template |

| | and executes it |

|-------------------------+---------------------------------------------|

| Keys other | Displays a character corresponding to the |

| than above | key on the command line and skips one |

| | character of the template |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Table 3.7 Template operation examples

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

| | | Contents of template ("-" |

| Keyboard input | Command line display | indicates location currently |

| | | referred to) |

|-------------------+----------------------+------------------------------|

| DIR ABCDE | A>DIR ABCDE | --------- |

| | | |

| RETURN | A> | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| DOWN | A>DIR ABCDE | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| LEFT LEFT LEFT | A>DIR AB | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| INS XYZ | A>DIR ABXYZ | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| RIGHT RIGHT RIGHT | A>DIR ABXYZCDE | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| UP | A> | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| DOWN | A>DIR ABCDE | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| UP | A> | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| XXX | A>XXX | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| DOWN | A>XXX ABCDE | DIR ABCDE |

| | | - |

| HOME | A>XXX ABCDE | XXX ABCDE |

| | | - |

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

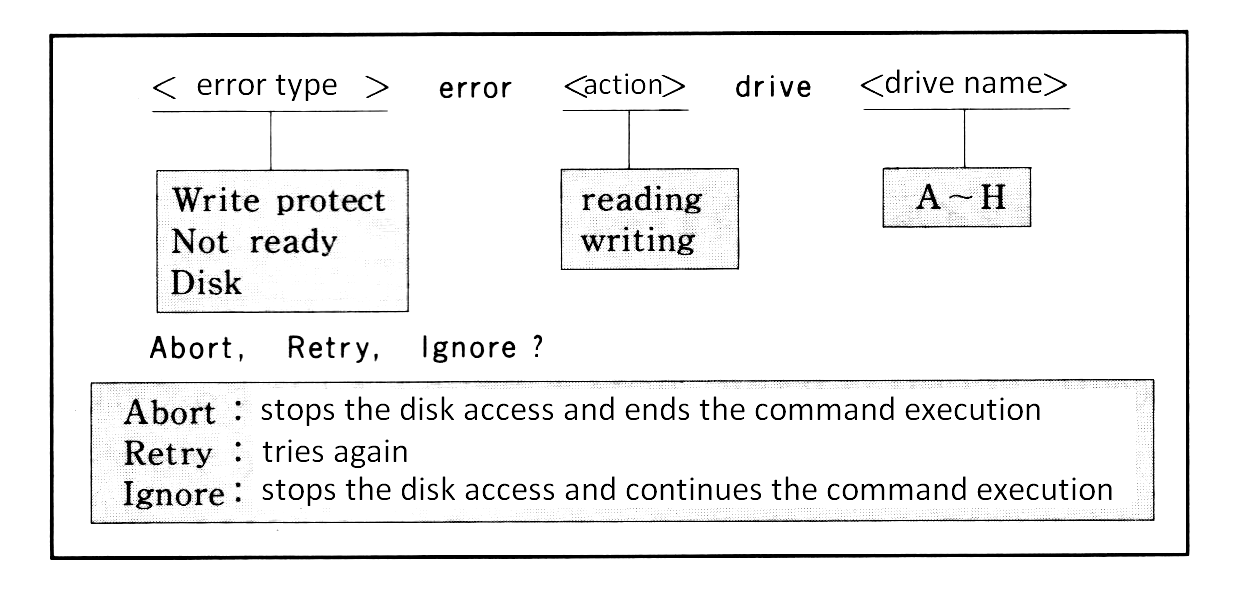

Disk errors

When an error occurs during disk access, MSX-DOS retries sometimes. Still more errors cause MSX-DOS to display the following message and inquire what to do with them. Press one of the keys A, R, or I.

Figure 3.5 Error display

The following error might occur other than listed above. It indicates that the pointer in FAT is pointing to a cluster which does not exist. When this error occurs, the diskette will be unusable.

Bad FAT

2.2 Internal commands

Internal commands are assembly language programs grouped together in COMMAND.COM. It is not necessary to read them from the disk so they are executed fast. Following are 13 internal commands. This section describes their use.

BASIC ........... jumps to MSX DISK-BASIC

COPY ............ copies a file

DATE ............ displays or modifies date

DEL ............. deletes a files

DIR ............. displays a list of files

FORMAT .......... formats a disk

MODE ............ modifies number of characters to be displayed in one line

PAUSE ........... pauses a batch command operation

REM ............. puts a comment line in a batch command

REN ............. renames a file name

TIME ............ displays or modifies time

TYPE ............ prints the contents of a file

VERIFY .......... turns on/off the verify mode

BASIC

form: BASIC [<file spec>]

Starts DISK-BASIC. This is not done by loading BASIC onto RAM but by selecting BASIC-ROM in 0000H to 7FFFH by switching the slot, so it starts immediately. When <file spec> is specified, the corresponding BASIC program is automatically read and executed. To return to the MSX-DOS environment from BASIC, execute “CALL SYSTEM”.

COPY

This command copies the contents of one file to another. Specifying parameters enables various options.

(1) File duplication

form: COPY <file spec 1> <file spec 2>

Duplicates the file specified by <file spec 1> into a file specified by <file spec 2>. Files having the same names cannot be created on the same disk. On different disks, specifying the same names is possible.

examples:

A>COPY ABC XYZ ⟵ copies file "ABC" and makes a file "XYZ".

A>COPY B:ABC XYZ ⟵ copies a file "ABC" on drive B and makes a file "XYZ".

A>COPY B:ABC C:XYZ ⟵ copies a file "ABC" on drive B and makes a file "XYZ" on drive C.

When copying files, either ASCII or binary mode may be selected. The “/A” swith specifies ASCII mode and the “/B” switch specifies binary mode. If no mode is specified, binary mode is selected by default (except when combining files, described in (4) below, when ASCII is the default mode). Table 3.8 shows the differences between the ASCII and the binary modes.

Table 3.8 ASCII mode and binary mode

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

| | Read from source file | Write to destination file |

|-----------+-----------------------------------+---------------------------|

|ASCII mode | ignore after 1AH (file end mark) | add one byte 1AH to end |

|Binary mode| read as long as physical file size| write without modification|

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

examples:

A>COPY/A ABC XYZ ⟵ ABC to XYZ (both files are in ASCII mode)

A>COPY ABC/A XYZ/B ⟵ reads ABC in ASCII mode and writes it to XYZ in binary mode

(2) File duplication to another disk drive

form: COPY <file spec> [<destination drive>:]

Copies a file specified by <file spec> to <destination drive> under the same file name. When <destination drive> is omitted, it is copied to the default drive. The drive name included in the <file spec> must not be the same as the <destination drive>.

More than one file can be copied by using wildcards in the <file spec>. In this case, the file name is displayed on the screen each time the file is copied.

examples:

A>COPY *.COM B: ⟵ copies any files with extension "COM" on default drive to drive B

A>COPY B:ABC ⟵ copies a file ABC to default drive

(3) Simultaneous duplication of many files

form:

COPY <file spec 1> <file spec 2>

------------- -------------

| |

wildcard description wildcard description

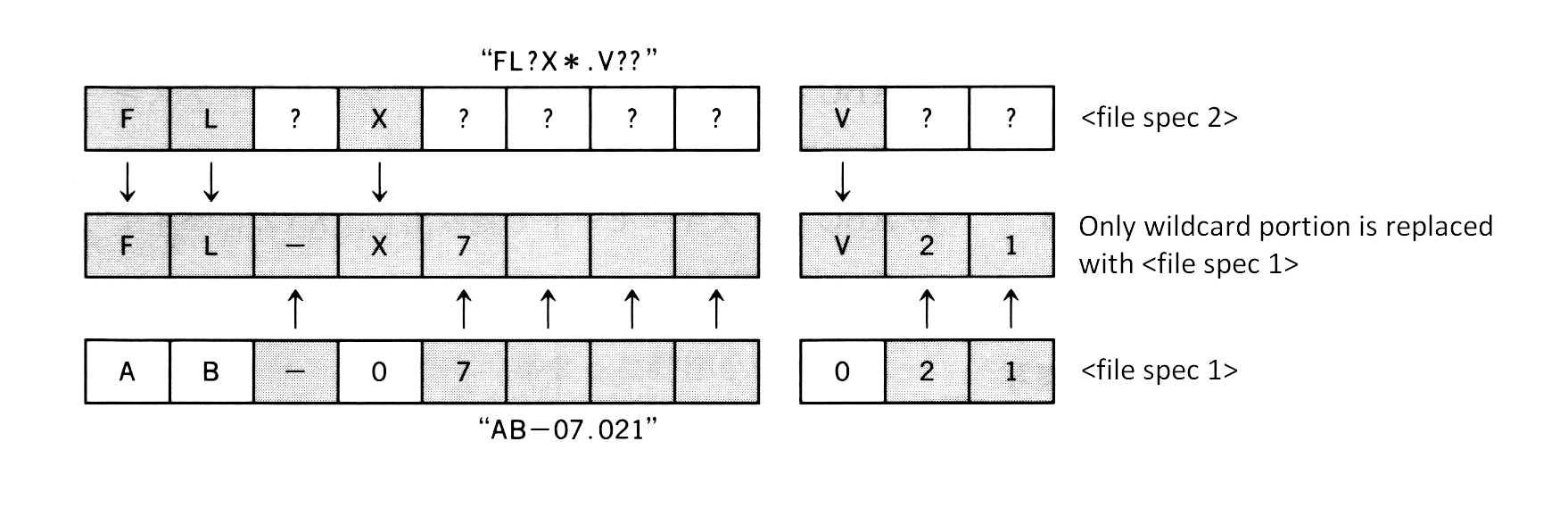

When <file spec 2>, the destination, is described using wildcards, the portions corresponding to wildcards are replaced with corresponding characters in <file spec 1>. For example, when

COPY AB-07.021 FL?X*.V??

is executed, it is interpreted as shown in figure 3.6 and a file “FL-X7.V21” is created.

Figure 3.6 Wildcard specification of destination file

Using wildcards in the specification of <file spec 1> enables the duplication of many files at the same time.

examples:

A>COPY *.ASM *.MAC ⟵ makes files with extension "MAC" from any files with extension "ASM"

A>COPY A*.* B:Z*.* ⟵ Any files beginning with the character A are copied to files beginning with

the character Z on drive B

(4) File concatenation

form:

COPY <multiple file spec> <file name>

--------------------

|

wildcard specification, or

multiple file spec connected by "+"

When one destination file receives more than one source file, the contents of all source files are concatenated and stored to the specified destination file. When specifying more than one source file, wildcards are available, and file specs can also be copied by using the plus sign.

When files are concatenated, ASCII mode is selected by default and 1AH is considered the file end mark. Thus, concatenating binary files including data 1AH by the COPY command causes data after 1AH to be discarded. To prevent this, specify /B switch and use COPY command in binary mode.

If more than one wildcard appears in the specification of source files, the second wildcard and after are expanded referring to original file names, as in paragraph (3) above. This permits concatenation of similar files at the same time.

examples:

A>COPY X+Y+Z XYZ ⟵ concatenates X, Y, AND Z and stores in a file XYZ

A>COPY *.LST ALL ⟵ concatenates any files with extension "LST" and stores in a file ALL

A>COPY /B *.DAT ALL ⟵ concatenates any ".DAT" files in binary mode

A>COPY ASC/A+BIN/B AB/B ⟵ concatenates an ASCII file ASC and a binary file BIN and stores in a file AB

A>COPY *.LST+*.REF *.PRN ⟵ concatenates files named same with extension "LST" and extension "REF"

and makes a file with extension "PRN"

DATE

form:

DATE [<month>-<day>-<year>]

- -

| |

-------

|

"/" and "." are also allowed.

Sets the date in the internal CLOCK-IC. For MSX machines without a CLOCK-IC, it is written to the specific work area. Creations or modifications of files on MSX-DOS cause this date information to be recorded for each file.

When the DATE command is executed without specifying <month>/<day>/<year>, the date currently set is displayed with a request for a new date as shown below. Pressing only the RETURN key here leaves the date unchanged.

Current date is <day of week> <month>-<day>-<year>

Enter new date:

The format of the date to be set by the DATE command has three fields: <year>, <month>, and <day>. Each field is separated by “-“, “/”, or “.”. Each field can have the following numerical values:

<year>: 1980 to 2079

0 to 79 (considered as 2000 to 2079)

80 to 99 (considered as 1980 to 1999)

<month>: 1 to 12

<day>: 1 to 31

Foreign versions of MSX-DOS have different date formats: <month>-<day>-<year> or <day>-<month>-<year>.

DEL

form: DEL <file spec>, ERASE is also allowed

Deletes the specified file. Wildcards can be used to specify more than one files.

Since DEL *.* causes all files on the diskette to be deleted, in this case, an acknowledgement is required.

A>DEL *.*

Are you sure (Y/N)?

Pressing “Y” or “y” causes all files to be deleted.

ERASE may be used the same way as the DEL command.

DIR

form: DIR [<file spec>] [/W] [/P]

The following information about the specified at <file spec> is listed from the left side in one line.

<file name> <file size> <date> <time>

The fields <date> and <time> show when the file was created or last modified. When this information is longer than one line, items displayed near the right side are omitted.

In addition to the usual wildcards, the following abbreviations for file spec can be used.

Abbreviation Formal notation

DIR = DIR *.*

DIR <drive>: = DIR <drive>:*.*

DIR <filename> = DIR <filename>.*

DIR .<extension> = DIR *.<extension>

When the /W switch is specified, only <filename>s are padded to one line. When the /P switch is specified, the listing is stopped after each display page to wait for any key input.

examples:

A>DIR ⟵ displays information for all files on drive A

A>DIR B: ⟵ displays information for all files on drive B

A>DIR TEST ⟵ displays information for all files having <filename> "TEST"

A>DIR /W ⟵ displays all file names of drive A

FORMAT

form: FORMAT

Formats a diskette in MSX-DOS format. In other words, directories and FAT are initialised and any files are erased. Since MSX-DOS has the same disk format as MS-DOS, the formatted diskette is also read or written by MS-DOS.

When executing the FORMAT command, an inquiry

Drive name? (A,B) (⟵ Depends on number of drives)

is made for the name of the drive containing a disk to be formatted. Answering “A” or “B” causes the menu to be displayed when a drive that can select one-sided and two-sided formats is being used. After specifying the type of format,

Strike a key when ready

is displayed to wait for a key input. Pressing any key starts formatting. See the disk drive manual for the format menu.

MODE

form: MODE <characters per line>

Sets the number of characters to be displayed in one line on the screen. <characters per line> can have a value from 1 to 80 and the screen mode depends on that value:

<characters per line> Screen mode

1 to 32 GRAPHIC 1 (SCREEN 1)

33 to 40 TEXT 1 (SCREEN 0:WIDTH 40)

41 to 80 TEXT 2 (SCREEN 0:WIDTH 80)

PAUSE

form: PAUSE [<comment>]

MSX-DOS has a “batch operation” feature which automatically executes a series of commands written in a text file. During the batch operation, you may want to stop command execution temporarily. One example would be for the user to exchange disks. PAUSE can be used in such cases.

When this command is executed,

Strike a key when ready...

is displayed and a key input is expected. Pressing any key other than Ctrl-C here ends the PAUSE command and proceeds to the next one. Pressing CTRL-C abandons the batch operation. Any kind of comments can follow “PAUSE”. This makes it possible to display the purpose of the request for the key input.

REM

form: REM [<comment>]

REM is used to write a comment in the batch command. It does nothing as a command. A space between “REM” and <comment> is required.

REN

form: REN <file spec> <file name>, RENAME is also allowed

REN changes the file name specified by <file spec>. Wildcards can be used in both <file spec> and <file name>. Specifying wildcards for <file name> causes these wildcards to be replaced with corresponding characters of the <file spec> (see COPY command).

Any attempt to change a file name to a name already in use will cause an error.

examples:

A>REN ABC XYZ ⟵ changes the file name "ABC" to "XYZ"

A>REN B:ABC XYZ ⟵ changes the file name "ABC" on drive B to "XYZ"

A>REN *.BIN *.COM ⟵ changes any files with the extension "BIN" to "COM"

TIME

form: TIME [<hour>[:<minute>[:<second>]]]

TIME sets the time for the internal CLOCK-IC. Nothing happens to machines that do not have a CLOCK-IC. When a file is created on MSX-DOS, time information set here is recorded for each file.

Executing the TIME command without specifying the time causes the current time setting to be displayed as shown below. Then there is an input request for a new time. Pressing only the RETURN key does not change the time.

Current time is <hour>:<minute>:<second>:<second/100><p or a>

Enter new time:

The punctuation mark “:” separates the three TIME command fields of <hour>, <minute>, and <second>. Fields after <minute> or <second> may be omitted or considered to be 0. Each field can have the following values:

<hour>: 0 to 23

12A (represents midnight)

0A to 11A (represents midnight to 11 o'clock in the morning)

12P (represents noon)

1P to 11P (represents 1 o'clock to 11 o'clock in the evening)

<minute>: 0 to 59

<second>: 0 to 59

examples:

A>TIME 12 ⟵ sets time to 12:00:00

A>TIME 1:16P ⟵ sets time to 13:16:00

TYPE

form: TYPE <file spec>

The command TYPE displays the contents of a file specified by <file spec>. Using wildcards in

VERIFY

form: VERIFY [ON|OFF]

VERIFY sets/resets the verify mode. When the verify mode is turned ON, after data is written to the disk, it is always read to ensure that it was written correctly. This is why disk access takes longer. “VERIFY OFF” is set by default.

2.3 Batch Command Usage

MSX-DOS has a batch feature that allows a series of commands listed in the order of operation to be executed automatically. The file containing this procedureis called a “batch file” and the series of operations defined by a batch file is called a “batch command”.

A batch file uses the extension “.BAT”. Typing only the file name (the extension “.bat” is not typed) at the command line prompt causes MSX-DOS to execute the commands in the file line by line.

For example, let us consider the following operation:

- Copy all files on drive A with the extension “.COM” onto drive B.

- List all “COM” files on drive B.

- Delete all “COM” files on drive A.

This operation could be achieved by issuing the following commands to MSX-DOS:

A>COPY A:*.COM B:

A>DIR B:*.COM /W

A>DEL A:*.COM

If these three lines are combined into a batch file called “MV.BAT”, the command line input “MV” will automatically execute the operation shown above. The following list illustrates this.

A>COPY CON MV.BAT -+

COPY A:*.COM B: | creates "MV.BAT"

DIR B:*.COM /W |

DEL A:*.COM -+

^Z Ctrl-Z + RETURN key input

A>TYPE MV.BAT -+

COPY A:*.COM B: | to confirm the contents of "MV.BAT"

DIR B:*.COM /W |

DEL A:*.COM -+

A>MV invokes the batch command "MV"

A>COPY A:*.COM B: reads the first line automatically and executes it

.

.

.

A>DIR B:*.COM /W reads the second line automatically and executes it

.

.

.

A>DEL A:*.COM reads the third line automatically and executes it

.

.

.

A batch operation may be interrupted by pressing Ctrl-C. When Ctrl-C is entered during batch operations, the request shown in Figure 3.7 is displayed on the screen.

Figure 3.7 Interrupt of the batch operation

-----------------------------------

| |

| Terminate batch file (Y/N)? |

| |

-----------------------------------

Selecting “Y” here terminates the batch command and returns to MSX-DOS. Selecting “N” reads the next line of the batch file and continues the execution of the batch command.

Batch variables

For more flexible use of the batch command, any string can be passed as parameters from the command line to the batch command. Parameters passed are referred to with the symbols “%n” where n is any number from 0 to 9. These “%n” symbols are called batch variables.

Batch variables %1, %2, … correspond to parameters specified in the command line from left to right, and %0 is for the name of the batch command itself.

Figure 3.8 Examples for batch variables usage

-----------------------------------------------------------------

| |

| A>COPY CON TEST.BAT ......... creates a batch command |

| REM %0 %1 %2 %3 |

| ^Z |

| 1 file copied |

| A>TYPE TEST.BAT |

| REM %0 %1 %2 %3 ...... a batch command to display 3 arguments |

| |

| A>TEST ONE TWO THREE FOUR ...... executes the batch command, |

| A>REM TEST ONE TWO THREE giving arguments to it |

| A> |

| |

-----------------------------------------------------------------

AUTOEXEC.BAT

The batch file named “AUTOEXEC.BAT” is used as a special autostart program at MSX-DOS startup. When MSX-DOS is invoked, COMMAND.COM examines whether AUTOEXEC.BAT exists and, if so, executes it.

2.4 External Commands

External commands exist on the diskette as files with the extension “.COM”, and typing the external command name (except for the extension) causes the command to be executed in the following manner.

- loads an external command after 100H

- calls 100H

Developing external commands

Assembly language routines created to work in memory at location 100H and saved under file names with the extension “.COM” are called external commands and can be executed from MSX-DOS.

For example, consider a program to produce a control code “0CH” by using one-character output routine (see system calls) and clear the screen. This is an 8-byte program as shown below.

List 3.1 Contents of CLS.COM

1E 0C LD E,0CH ; E := control-code of CLS

0F 02 LD C,02H ; C := function No. of CONSOLE OUTPUT

CD 05 00 CALL 0005H ; call BDOS

C9 RET

Writing these 8 bytes to a file named CLS.COM produces the external command “CLS” to clear the screen. The following sample program uses the sequential file access feature of BASIC to make this command. After this program is run, the CLS command is created on the diskette. Confirm that the command actually works after returning to MSX-DOS.

List 3.2 Creating CLS.COM

100 '***** This program makes "CLS.COM" *****

110 '

120 OPEN "CLS.COM" FOR OUTPUT AS #1

130 '

140 FOR I=1 TO 8

150 READ D$

160 PRINT #1,CHR$(VAL("&H"+D$));

170 NEXT

180 '

190 DATA 1E,0C,0E,02,CD,05,00,C9

Passing arguments to an external command

When creating an external command, there are two ways to pass arguments from the command line to the external command. First, when passing the file names to the command line as arguments, use 5CH and 6CH in the system scratch area. COMMAND.COM, which always considers the first and second parameters as file names when external commands are executed, expands them to a drive number (1 byte) + file name (8 bytes) + extension (3 bytes) and stores them in 5CH and 6CH. These are in the same format as the first 12 bytes of FCB, so setting these address as first addresses of FCB permits various operatuons.

However, since in this method only 16 bytes differ from the starting addresses of two FCBs, either 5CH or 6CH (only) can be used as a complete FCB. Next, when passing arguments other than file names (numbers, for instance) or creating an external command handling more than three file names, COMMAND.COM stores the whole command line, which invoked the external command, except for the command line itself in the form of number of bytes (1 byte) + command line body, so it can be used by interpreting it in the external command properly. See List 3.3 of section 4 for an example of passing arguments using this DMA area.

3. STRUCTURE OF DISK FILES

Information about the structure of data on the disk and how it is controlled is important when acessing the disk using system calls. This section begins with a description about “logical sectors” which are the basic units for exchanging data with the disk on MSX-DOS, and proceeds to the method of handling data with “files” which is more familiar to programmers.

3.1 Data units on the disk

Sectors

MSX-DOS can access most types of disk drives including th 3.5 inch 2DD and hard disks. For handling different media in the same way, the system call consider “logical sector” as the basic units of data on the disk. A logical sector is specified by numbers starting from 0.

Clusters

As long as system calls are used, a sector may be considered the basic unit of data as considered above. In fact, however, data on the disk is controlled in units of “clusters” which consists of multiple sectors. As described later in the FAT section, a cluster is specified by a serial number from 2 and the top of the data area corresponds to the location of cluster #2. For getting information about how many sectors a cluster has, use the system call function 1BH (acquiring disk information).

Conversion from clusters to sectors

In a part of the directory or FCB, described later, the data location on the disk is indicated by the cluster. To use system calls to access data indicated by cluster, the relation of the correspondence between the cluster and the sector needs to be calculated. Since cluster #2 and the top sector of the data area reside in the same location, this can be done as follows:

- Assume the given cluster number is C.

- Examine the top sector of the data area (by reading DPB) and assume it is S0.

- Examine the number of sectors equivalent to one cluster (using function 1BH) and assume it is n.

- Use the formula

S = S0 + (C-2) * nto calculate sector numbers.

In MSX-DOS, sectors in the disk are divided into four areas, as shown in Table 3.9. The file data body written to the disk is recorded in the “data area” portion. Information for handling data is written in three areas. Figure 3.9 shows the relation of the locations of these areas. The boot sector is always in sector #0, but the top sectors (FAT, directory, and data area) differ by media, so DPB should be referred to.

Table 3.9 Disk contents

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

| boot sector | MSX-DOS startup program and information proper to the disk |

| FAT | physical control information of data on the disk |

| directory | control information of files on the disk |

| data area | actual file data |

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Figure 3.9 Relation of locations of elements in the disk

+- ----------------------- ⟵ sector #0

| | boot sector |

| |---------------------| ⟵ sector #? -+

| | FAT | | Top sectors of these data

whole |---------------------| ⟵ sector #? | areas can be acquired by

of a | directory | | referring to DPB.

disk |---------------------| ⟵ sector #? -+

| | |

| | data area |

| | |

+- ----------------------- ⟵ last sector

DPB (drive parameter block) and boot sector

On MSX-DOS, the area “DPB” is allocated in the work area of memory for each connected drive, and information proper to each drive is recorded there. MSX-DOS can handle most types of disk drives, because the differences between media can be compensated for by the process corresponding to each drive.

Information written on DPB, which is originally on the boot sector (sector #0) of the disk, is read at MSX-DOS startup. Note that the differences between the contents of the boot sector and DPB, as shown in Figures 3.10 and 3.11. Data is arranged differently in the boot sector and the DPB.

Figure 3.10 Information of the boot sector

| |

|---------------| -+

0B | | |-- 1 sector size (in bytes)

0C | | |

|---------------| -+

0D | | ---- 1 cluster size (in sectors)

|---------------| -+

0E | | |-- Number of unused sectors by MSX-DOS

0F | | |

|---------------| -+

10 | | ---- Number of FATs

|---------------| -+

11 | | |-- Number of directory entries (How many files can be created)

12 | | |

|---------------| -+

13 | | |-- Number of sectors per disk

14 | | |

|---------------| -+

15 | | ---- Media ID

|---------------| -+

16 | | |-- Size of FAT (in sectors)

17 | | |

|---------------| -+

18 | | |-- Number of tracks per sector

19 | | |

|---------------| -+

1A | | |-- Number of sides used (either one or two)

1B | | |

|---------------| -+

1C | | |-- Number of hidden sectors

1D | | |

|---------------| -+

| |

Figure 3.11 DPB structure

-----------------

BASE -> | | ---- drive number

|---------------|

+1 | | ---- media ID

|---------------| -+

+2 | | |-- sector size

+3 | | |

|---------------| -+

+4 | | ---- directory mask

|---------------|

+5 | | ---- directory shift

|---------------|

+6 | | ---- cluster mask

|---------------|

+7 | | ---- cluster shift

|---------------| -+

+8 | | |-- top sector of FAT

+9 | | |

|---------------| -+

+10 | | ---- number of FATs

|---------------|

+11 | | ---- number of directory entries

|---------------| -+

+12 | | |-- top sector of data area

+13 | | |

|---------------| -+

+14 | | |-- amount of cluster + 1

+15 | | |

|---------------| -+

+16 | | ---- number of sectors required for one FAT

|---------------| -+

+17 | | |-- top sector of directory area

+18 | | |

|---------------| -+

+19 | | |-- FAT address in memory

+20 | | |

----------------- -+

Use the system call Function 1BH (disk information acquisition) to access the DPB. This system call returns the DPB address in memory and other information for each drive written on the boot sector (see section 4 “System call usage” for the detailed usage).

FAT (file allocation table)

In MSX-DOS, a “cluster” is the data unit for writing to the disk. Files larger than a cluster are written across multiple clusters. But in this case adjacent clusters are not always used. In particular, after creating and deleting files many times, clusters which are no longer used are scattered at random across the disk. When a large file is created for such cases, the file is broken down into several clusters and these clusters are stored where space is available. The linkage information is kept at the beginning so that the file can be recreated. This is the main function of the FAT.

When a bad cluster is found, FAT is also used to record that location, so access will not be made there any more. Linkage information of clusters and information concerning bad clusters is necessary for managing disk files. Without this information, the whole disk will be unusable. For this reason, more than one FAT is always prepared in case of accidental erasure.

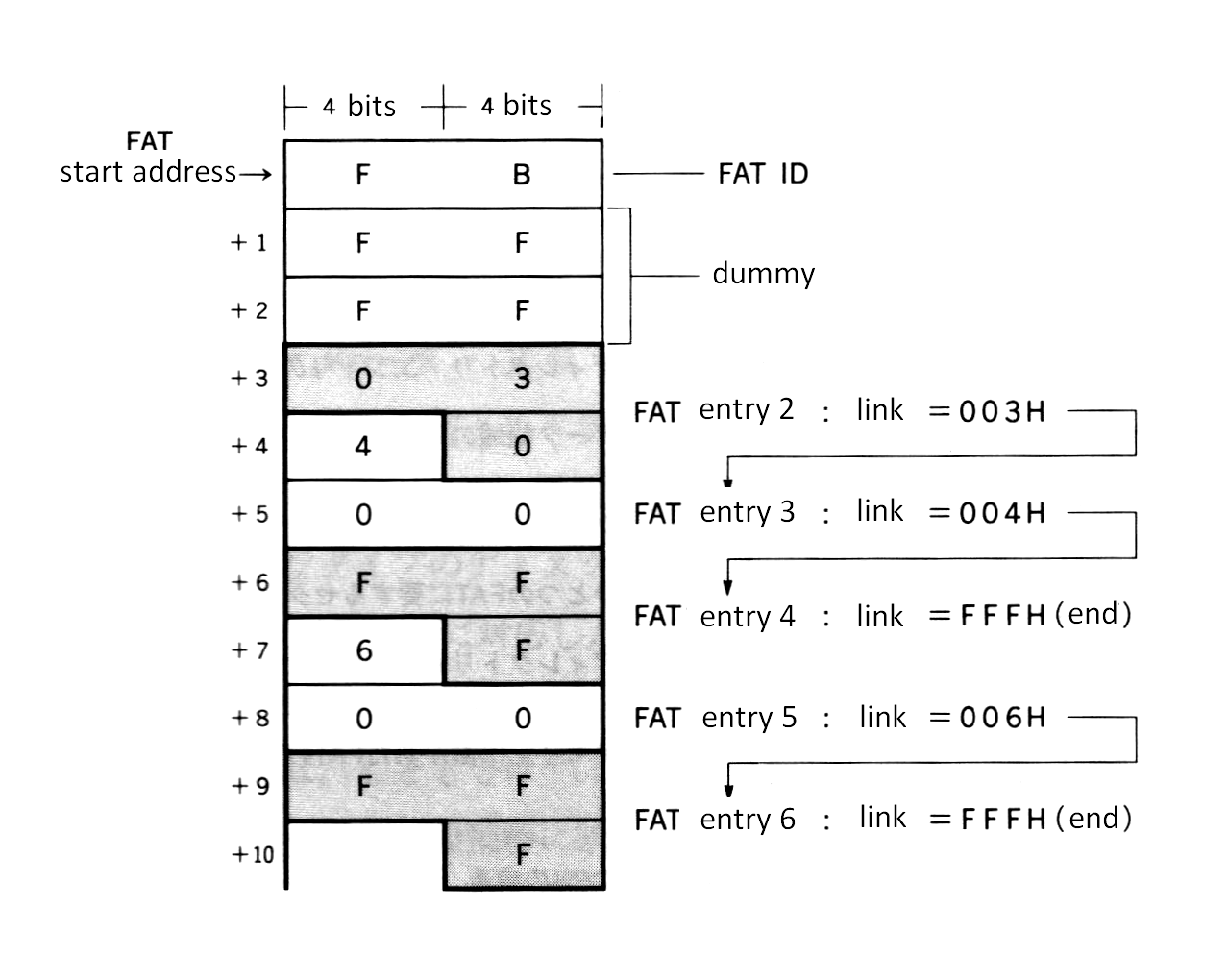

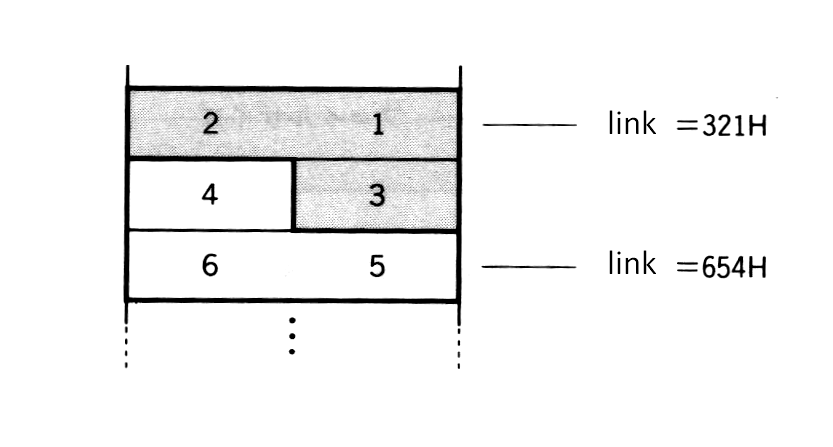

Figure 3.2 shows an example of a FAT. The first byte is called the “FAT ID” which contains the value indicating the type of media (the same value as media ID in Table 3.1). The next two bytes contains meaningless dummy values. From the fourth byte (start address + 3), actual linkage information is recorded in an irregular format of 12 bits per cluster. Each 12-bit area containing linkage information is called a FAT entry. Note that the FAT entry begins with number 2. The number of the FAT entry is also the number of the cluster corresponding to it. Read the 12-bit linkage information recorded in the FAT entry in the way shown in Figure 3.13.

Figure 3.12 FAT example

The linkage information is the value indicating the next cluster number. FFFH means that the file ends with that cluster. The example of Figure 3.12 shows a file of three clusters, (cluster #2 -> cluster #3 -> cluster #4), and a file of two clusters, (cluster #5 -> cluster #6). The linkage from the cluster with the smaller number is only for easy comprehension. In actual practice, numbers are not necessarily ordered.

Figure 3.13 Reading FAT

Directory

The FAT as described above, relates the physical location of data on the disk and does not include information about the contents of data written there. Thus, an information resource other than FAT is required to know what kind of data is in a file. This resource is called a “directory”. A directory entry is composed of 32 bytes and records file names, file attributes, date created, time created, number of the top cluster of the file, and file size, as shown in Figure 3.14.

“File attributes” in the directory are used for specifying the invisibility attribute in a file. Specifying “1” in the second bit from the lowest of this byte prevents files specified in the directory from being accessed by the system call (see Figure 3.15). MS-DOS also has a file attribute byte which permits a write-prohibit attribute using another bit, but MSX-DOS does not support this feature.

The date and time are recorded so that two bytes of each are divided into three bitfields, as shown in Figure 3.16 and Figure 3.17. Since only 5 bits are prepared for the “time” bitfield, the minimum unit for time is two seconds. The year (1980 to 2079) is specified by using 0 to 99 in 7 bits.

Figure 3.14 Directory construction

Directory ----------------- -+

header --> | . | |

. |-- filename (8 characters)

. |

+7 | | |

|---------------| -+

+8 | | |

+9 | | |-- extension (3 characters)

+10 | | |

|---------------| -+

+11 | | ---- file attribute

|---------------| -+

. | . | |

. . |-- space for compatibility with MS-DOS

. . | (not used by MSX-DOS)

| | |

|---------------| -+

+22 | | |-- time created

+23 | | |

|---------------| -+

+24 | | |-- date created

+25 | | |

|---------------| -+

+26 | | |-- top cluster of the file

+27 | | |

|---------------| -+

+28 | | |

+29 | | |-- file size

+30 | | |

+31 | | |

----------------- -+

Figure 3.15 Invisibility attribute of the file

(11th byte of the directory)

---------------------------------

| . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . |

---------------------------------

|

| 0 : enables normal acess

+----->

1 : disables access

Figure 3.16 Bitfield representing time

(23rd byte of the directory) (22nd byte of the directory)

--------------------------------- ---------------------------------

| h4| h3| h2| h1| h0| m5| m4| m3| | m2| m1| m0| s4| s3| s2| s1| s0|

--------------------------------- ---------------------------------

| | | |

+-------------------+-----------------------------+-------------------+

hour (0 to 23) minute (0 to 59) second /2 (0 to 29)

|

"second" value when multiplied by 2 --+

Figure 3.17 Bitfield representing date

(25th byte of the directory) (24th byte of the directory)

--------------------------------- ---------------------------------

| y6| y5| y4| y3| y2| y1| y0| m3| | m2| m1| m0| d4| d3| d2| d1| d0|

--------------------------------- ---------------------------------

| | | |

+---------------------------+---------------------+-------------------+

year (0 to 99) month (1 to 12) day (1 to 31)

|

+-- corresponds to 1980 to 2079

The place where this directory information is actually recorded is the directory area on the disk (see Figure 3.9). The location (top sector) is recorded in the DPB. Directory entries (locations of directory storage) are arranged every 32 bytes in the driectory area, as shown in Figure 3.18. When a file is created, the directory is created at the lowest value of unused directory entries. Deleting a file causes E5H to be written to the first byte of the corresponding directory entry, which is empty. After all direcotry entries are exhausted, new files cannot be created even if there is a lot of unused space on the disk. The number of directory entries, that is, the number of files which can be created on one disk is also recorded in the DPB.

Figure 3.18 Organisation of directory area

|------ 32 bytes -------|

-------------------------

BASE -> | MSXDOS.SYS |

|-----------------------|

+32 | COMMAND.COM |

|-----------------------|

+64 | E5H | | ⟵ The directory entry whose first byte is E5H is currently unused

|-----------------------|

+96 | TEST |

|-----------------------|

| . |

. |

.

| |

|-----------------------|

+32 * n | 00H | | ⟵ The directory entry whose first byte is 00H has never been used

|-----------------------|

| |

3.2 File Access

FCB (file control block)

Using information recorded in the directory area allows data to be treated as a “file”. The advantage of this method is that the data location is not represented by an absolute number such as sector number or cluster number; instead, the file can be specified with a “name”. The programmer need only specify the file name and the system will do all the work concerned with accessing the requested file. In other words, the programmer need not understand the details of which sectors the file occupies. In this case, FCB plays an important role for directories.

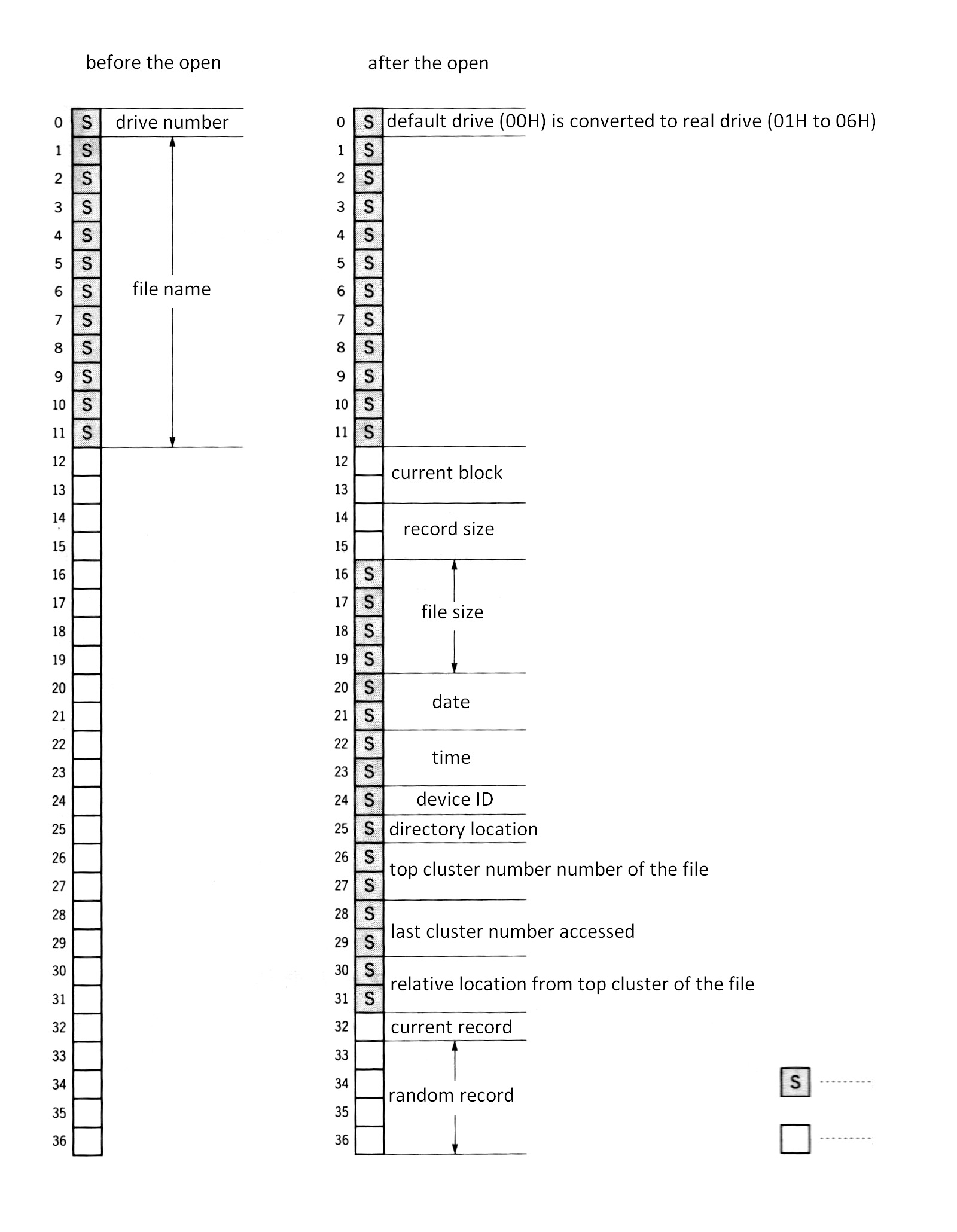

FCB is the area for storing information needed to handle files using system calls. Handling one file requires 37 bytes of memory each, as shown in Figure 3.19. Although the FCB can be located anywhere in memory, the address 005CH is normally used to utilize MSX-DOS features.

Figure 3.19 Organization of FCB

FCB ------

bytes | 0 | drive number

from |----|

top | 1 | file name

| | | filename ..... 8 bytes

V | 11 | extension .... 3 bytes

|----|

| 12 | current block

| 13 | number of blocks from the top of the file to the current block

|----|

| 14 | record size

| 15 | 1 to 65535

|----|

| 16 | file size

| | 1 to 4294967296

| 19 |

+-- |----|

| | 20 | date

| | 21 | same form as directory

(1) |----|

| | 22 | time

| | 23 | same form as directory

+-- |----|

| | 24 | device ID

| |----|

| | 25 | directory location

| |----|

| | 26 | top cluster number of the file

(2) | 27 |

| |----|

| | 28 | last cluster number accessed

| | 29 |

| |----|

| | 30 | relative location from top cluster of the file

| | 31 | number of clusters from top of the file to the last cluster accessed

+-- |----|

| 32 | current record

|----|

| 33 | random record

| | record order from the top of the file

| 36 | usually stores the last record made random access

------

Notes: FCB usages differ, depending on whether they use CP/M compatible system calls or additional system calls. See the decription below for details.

(1) When using version 2 of MSX-DOS, here is stored the volume-id of the disk, and should not be modified by the program. (2) When using version 2 of MSX-DOS, here is stored internal information relative to the physical location of the file on the disk. The format of this information is different from shown in figure 3.19, and should not be modified by the program.

-

drive number (00H) Indicates the disk drive containing the file. (0 -> default drive, 1 -> A:, 2 -> B:…)

-

filename (01H to 08H) A filename can have up to 8 characters. When it has less than 8, the rest are filled in by spaces (20H).

-

extension (09H to 0BH) A extension can have up to 8 characters. When it has less than 3, the rest are filled in by spaces (20H).

-

current block (0CH to 0DH) Indicates the block number currently being referred to by sequential access (see function 14H, 15H in section 4).

-

record size (0EH to 0FH) Specifies the size of data unit (record) to be read or written at one access, in bytes (see function 14H, 15H, 21H, 27H, 28H).

-

file size (10H to 13H) Indicates the size of the file in bytes.

-

date (14H to 15H) Indicates date when a file was last written. The format is the same as the one recorded in the directory.

-

time (16H to 17H) Indicates time when a file was last written. The format is the same as the one recorded in the directory.

-

device ID (18H) When a peripheral is opened as a file, the value shown in Table 3.10 is specified for this device ID field. For normal disk files, the value of this field is 40H + drive number. For example, the device ID for drive A is 40H (for future expansion, application programs should not use the ID byte).

Table 3.10 Device ID

----------------------------------

| Device name | Device ID |

|--------------------+-----------|

| CON (Console) | 0FFH |

| PRN (Printer) | 0FBH |

| LST (List=Printer) | 0FCH |

| AUX (Auxiliary) | 0FEH |

| NUL (Null) | 0FDH |

----------------------------------

-

directory location (19H) Indicates the order of the directory entries of a file in the directory area.

-

top cluster (1AH to 1BH) Indicates the top cluster of the file in the disk.

-

last cluster accessed (1C to 1DH) Indicates the last cluster accessed.

-

relative location from top cluster of last cluster accessed (1EH to 1FH) Indicates the relative location from the top cluster of the last cluster accessed.

-

current record (20H) Indicates the record currently being referred to by sequential access (see function 14H, 15H).

-

random record (21H to 24H) Specifies a record to be accessed by random access or random block access. Specifying a value from 1 to 63 for the record size field described above causes all four bytes from 21H to 24H to be used, where only three bytes from 21H to 23H have meaning when the record size is greater than 63 (see function 14H, 15H, 21H, 22h, 27H, 28H).

Opening a file

A special procedure is required to open a file when using FCB. “Opening a file” means, at the system call level, transforming the incomplete FCB whose file name field is only defined for the complete FCB, by using information written in the directory area. Figure 3.20 shows the differences between “unopened FCB” and “opened FCB”.

Figure 3.20 Before/after opening FCB

Closing a file

When a file is opened and written to, the contents of each field of FCB, such as size, is also modified. Unless the updated FCB information is returned to the directory area, directory information and the actual contents of the file might be different at the next file access. This operation to return the updated FCB information to the directory corresponds to closing a file at the system call level.

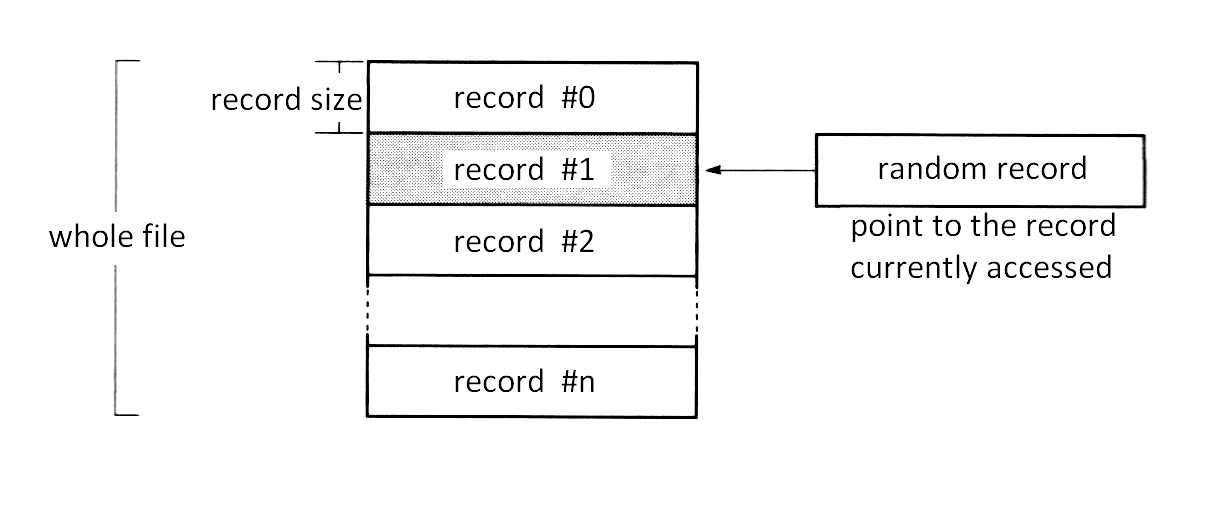

Random block access (file management by records)

MSX-DOS has two system calls dealing with random access, “RANDOM BLOCK READ” and “RANDOM BLOCK WRITE”. With these system calls, a file can be divided into data units of any size, which can be handled by numbers, such as 0, 1, 2, …, from the top. This data unit is called a “record”. Record size can be any value of more than one byte. So, treating a whole file as one record (extreme sequential access), treating data with one byte as one record (extreme random access), or treating 128 bytes as one record (the CP/M way) are all possible.

In this case, the FCB fields, “record size” and “random record” are used to specify the record. The value of the record size field is the number of bytes in one record. Random record fields can have any record number to be accessed (for more detailed usage, see descriptions of each system call).

Figure 3.21 File and record

Sequential access (file management by fixed-length record + current record + current block)

MSX-DOS can also access files the same way as CP/M for purposes of compatibility. One way is the sequential file which is managed by “current record” and “current block”. This uses a 128-byte fixed-length record as the basic unit of data. File access is always done from the top sequentially and the number of records which was accessed is counted at the current record field of FCB. The value of the current record field is reset to 0 when it reaches 128, and the carry is counted in the current block field.

Random access (file management by fixed-length record + random record)

A second method included to keept compatibility with CP/M is a random access method using random record fields. It can access the record of any location but the record size is fixed at 128 bytes.

4. SYSTEM CALL USAGE

The system calls are a collection of general-purpose subroutines which handle the basic input/output operations of MSX-DOS. Having these system calls gathered into BIOS in a predefined manner permits the basic functions of the MSX disk system to be easily accessed.

There are two purposes of system calls; first, to reduce programming time by preprogramming basic functions; second, to increase portability by the fact that all programs share the same basic functions. Utilizing system calls shortens program development time and makes the developed program highly portable.

To execute a system call, enter the defined function number in the C register of the Z80 CPU and call one of the following addresses:

0005H ................. MSX-DOS

F37DH (&HF37D) ........ MSX DISK-BASIC

For example, when the function number is 01FH and the system call requires 00H to be set in the A register, the following assembler code can be used with MSX-DOS:

LD A,00H

LD C,01FH

CALL 0005H

.

.

.

The CALL statement is also used in operations that return values or restore registers from memory. System calls can also be used from DISK-BASIC by using the entry address of F37DH. For this case, store the machine codes in the area allocated by the CLEAR statement and call its start address using the USR function.

System call format

This section introduces system call usages in the following notation:

- Function: function number

- Setup: value needed to be set in register or memory by programmer

- Return value: value set in register by system call

Function:

The function number is used to identify the system call. When using a system call, set the function number in the C register.

Setup:

In this section, “setup:” indicates the value to be set in the named register or memory location before executing system calls.

Return value:

The result obtained by a system call is normally set in a register or memory location. This is called output in this section and “return value:” indicates where and how this output is set.

Is important to note that when using system calls, the contents of registers other than those specified are sometimes destroyed. So, before using system calls, store the contents of registers whose value you do not want to change in an appropriate place (stack, for example) before executing system calls.

There are forty-two MSX system calls. These are listed in Table 3.11, and are described in this section. There are four categories:

- Peripheral I/O

- Environment setting

- Absolute READ/WRITE (direct access to sector)

- File access using FCB

Table 3.11 List of System Calls

| Function no. | Function |

|---|---|

| 00H | system reset |

| 01H | get one character from console (input wait, echo back, control code check) |

| 02H | send one character to console |

| 03H | get one character from auxiliary device |

| 04H | send one character to auxiliary device |

| 05H | send one character to printer |

| 06H | get one character from console (no input wait, no echo back, no control code check) / one character output |

| 07H | get one character from console (input wait, no echo back, no control code check) |

| 08H | get one character from console (input wait, no echo back, control code check) |

| 09H | send string |

| 0AH | get string |

| 0BH | check input from console |

| 0CH | get version number |

| 0DH | disk reset |

| 0EH | select default drive |

| 0FH | open file |

| 10H | close file |

| 11H | search the first file matched with wildcard |

| 12H | search the second and after the second file matched wildcard |

| 13H | delete file |

| 14H | read sequential file |

| 15H | write sequential file |

| 16H | create file |

| 17H | rename file |

| 18H | get login vector |

| 19H | get default drive name |

| 1AH | set DMA address |

| 1BH | get disk information |

| 1CH-20H | no function |

| 21H | write random file |

| 22H | read random file |

| 23H | get file size |

| 24H | set random record field |

| 25H | no function |

| 26H | write random block |

| 27H | read random block |

| 28H | write random file (00H is set to unused portion) |

| 29H | no function |

| 2AH | get date |

| 2BH | set date |

| 2CH | get time |

| 2DH | set time |

| 2EH | set verify flag |

| 2FH | read logical sector |

| 30H | write logical sector |

Note: System call function numbers are from 00H to 30H; the following seven numbers are blank: 1CH to 20H, 25H, 29H

Calling these blank function system calls do nothing except setting 00H in the A register. System calls after function 31H are undefined. Using them may cause unpredictable results (not advisable).

List 3.3 Utility routines

;**************************************************************

;

; List 3.3 utility.mac

;

; these routines are used in other programs

;

; GETARG, STOHEX, PUTHEX, PUTCHR, DUMP8B

;

;**************************************************************

;

PUBLIC GETARG Note: Five utility routines included in

PUBLIC STOHEX this program list will be used in

PUBLIC PUTHEX sample programs later.

PUBLIC PUTCHR

PUBLIC DUMP8B

BDOS: EQU 0005H

DMA: EQU 0080H

;----- DE := address of arg(A)'s copy -----

GETARG: PUSH AF Note: Nth parameter (N is specified by

PUSH BC A register) of the command line

PUSH HL stored in default DMA area

(0080H to ) is loaded in memory and

LD C,A its starting address is returned in

LD HL,DMA DE register.

LD B,(HL)

INC HL

INC B

SKPARG: DEC B

JR NZ,NOARG

SKP1: LD A,(HL)

INC HL

CALL TERMCHK

JR NZ,SKP1

SKP2: LD A,(HL)

INC HL

CALL TRMCHK

JR Z,SKP2

DEC HL

DEC C

JR NZ,SKPARG

CPYARG: LD DE,BUFMEM

CPY1: LD A,(HL)

LD (DE),A

INC HL

INC DE

CALL TRMCHK

JR NZ,CPY1

DEC DE

LD A,"$"

LD (DE),A

LD DE,BUFMEM

JR EXIT

NOARG: LD DE,BUFMEM

LD A,"$"

LD (DE),A

EXIT: POP HL

POP BC

POP AF

RET

TRMCHK: CP 09H

RET Z

CP 0DH

RET Z

CP " "

RET Z

CP ";"

RET

;----- HL := hexadecimal value of [DE] -----

SOTHEX: PUSH AF Note: Hexadecimal string indicated by

PUSH DE DE register is converted into

LD HL,0000H two-byte integer and stored in

CALL STOH1 HL register.

POP DE

POP AF

RET

STOH1: LD A,(DE)

INC DE

SUB "0"

RET C

CP 10

JR C,STOH2

SUB "A"-"0"

RET C

CP 6

RET NC

ADD A,10

STOH2: ADD HL,HL

ADD HL,HL

ADD HL,HL

ADD HL,HL

OR L

LD L,A

JR STOH1

;----- print A-reg, in hexadecimal form (00-FF) -----

PUTHEX: PUSH AF Note: Contents of A register is displayed

RR A using two hexadecimal digits.

RR A

RR A

RR A

CALL PUTHX1

POP AF

PUTHX1: PUSH AF

AND 0FH

CP 10

JR C,PUTHX2

ADD A,"A"-10-"0"

PUTHX2: ADD A,"0"

CALL PUTCHR

POP AF

RET

;----- put character -----

PUTCHR: PUSH AF

PUSH BC

PUSH DE

PUSH HL

LD E,A

LD C,02H

CALL BDOS

POP HL

POP DE

POP BC

POP AF

RET

;----- dumps 8bytes of [HL] to [HL+7] in hexa & ASCII form -----

DUMP8B: PUSH HL Note: Contents of eight bytes after the

LD B,8 address indicated in HL register

DUMP1: LD A,(HL) are dumped in both hexadecimal

INC HL and character codes.

CALL PUTHEX

LD A," "

CALL PUTCHR

DJNZ DUMP1

POP HL

LD B,8

DUMP2: LD A,(HL)

INC HL

CP 20H

JR C,DUMP3

CP 7FH

JR NZ,DUMP4

DUMP3: LD A,"."

DUMP4: CALL PUTCHR

DJNZ DUMP2

LD A,0DH

CALL PUTCHR

LD A,0AH

CALL PUTCHR

RET

;----- work area -----

BUFMEM: DS 256

END

4.1 Peripheral I/O

The following system calls are intended for input/output operations. Some examples include console I/O (screen/keyboard), auxiliary I/O (external input/output), and printer I/O. Since subroutines such as getting information from the keyboard or controlling printers are necessary for most programs, you will find the system calls described in this section useful for general programming.

Console input

- Function: 01H

- Setup: none

- Return value: A register ⟵ one character from console

When there is no input (no key pressed and input buffer empty), an input is wait for. Input characters are echoed back to the console. The following control character input is allowed: Ctrl-C causes program execution to be halted and a return to the MSX-DOS command level; Ctrl-P causes any sucessive input to also echoed to the printer until Ctrl-N is accepted; Ctrl-S causes the display to stop until any key is pressed.

Ctrl-C ........ system reset

Ctrl-P ........ printer echo

Ctrl-N ........ halt printer echo

Ctrl-S ........ pause display

Console output

- Function: 02H

- Setup: E register ⟵ character code to be sent out

- Return value: none

This system call displays the character specified by the E register on the screen. It also checks the four control characters, listed above.

External input

- Function: 03H

- Setup: none

- Return value: A register ⟵ one character from AUX device

This system call checks four control characters.

External output

- Function: 04H

- Setup: E register ⟵ character code to send to AUX device

- Return value: none

This system call checks four control characters.

Printer output

- Function: 05H

- Setup: A register ⟵ one character from console

- Return value: ```

This system call does not echo back. It treats control characters in the same way as function 01H.

Direct console input/output

- Function: 06H

- Setup: E register ⟵ character code to be send to the console. When 0FFH is specified, the character will be input from the console.

- Return value: When the E register is set to 0FFH (input), the result of input is in the A register. The value set in the A register is the character code of the key, if it was pressed; otherwise, the value is 00H. When the E register is set to a value other than 0FFH (output), there is no return value.

This system call does not support control characters and does not echo back input. This system call checks four control characters.

Direct console input - 1

- Function: 07H

- Setup: none

- Return value: A register ⟵ one character from console

This system call does not support control characters, nor echo back.

Direct console input - 2

- Function: 08H

- Setup: none

- Return value: A register ⟵ one character from console

This system call does not echo back. It treats control characters in the same way as function 01H.

String output

- Function: 09H

- Setup: DE register ⟵ starting address of string, prepared on memory, to be sent to the console.

- Return value: none

24H (“$”) is appended to the end of the string as the end symbol. This system call checks and performs four control character functions, as listed previously.

String input

- Function: 0AH

- Setup: The address of memory where the maximum number of input characters (1 to 0FFH) is set should be set in the DE register.

- Return value: Number of characters actually sent from console is set in the address, one added to the address indicated by the DE register; string sent from console is set in the area from the address, two added to the address indicated by the DE register.

Return key input is considered as the end of console input. However, when the number of input characters exceeds the specified number of characters (contents indicated by DE register, 1 to 255), characters within the specified number of characters will be treated as an input string and set in memory, and the operation ends. The rest of characters including the return key are ignored. Editing with the template is available to string input using this system call. This system call checks and performs four control character function, as listed previously.

Console status check

- Function: 0BH

- Setup: none

- Return value: 0FFH is set in the A register when the keyboard is being pressed; otherwise, 00H is set.

This system call checks and performs four control character function, as listed previously.

4.2 Environment Setting and Readout

The following system calls set the MSX system environment; for example, changing the default drive, or setting various default values of the system.

System reset

- Function: 00H

- Setup: none

- Return value: none

When this is called in MSX-DOS, the system is reset by jumping to 0000H. When MSX DISK-BASIC call this, it is “warm started”. That is, it returns to BASIC command level without destroying programs currently loaded.

Version number acquisition

- Function: 0CH

- Setup: none

- Return value: HL register ⟵ 0022H

This system call is for acquiring various CP/M version numbers, on MSX-DOS, however, 0022H is always returned.

Disk reset

- Function: 0DH

- Setup: none

- Return value: none

If there is a sector which has been changed but not written to the disk, this system call writes it to the disk, then it sets the default drive to drive A and sets DMA to 0080H.

Default drive setting

- Function: 0EH

- Setup: E register ⟵ default drive number (A = 00H, B = 01H, …)

- Return value: none

Disk access by the system calls are made to the drive indicated by the default drive number, unless otherwise specified. Note that, when the drive number, which is set in the FCB specified upon calling the system call, is other than 00H, the default drive setting made by this system call is ignored.